In an effort to restrict abortion access, Wyoming Republicans authored a bill that could choke access to a host of life-saving medical procedures, from chemotherapy to heart surgery.

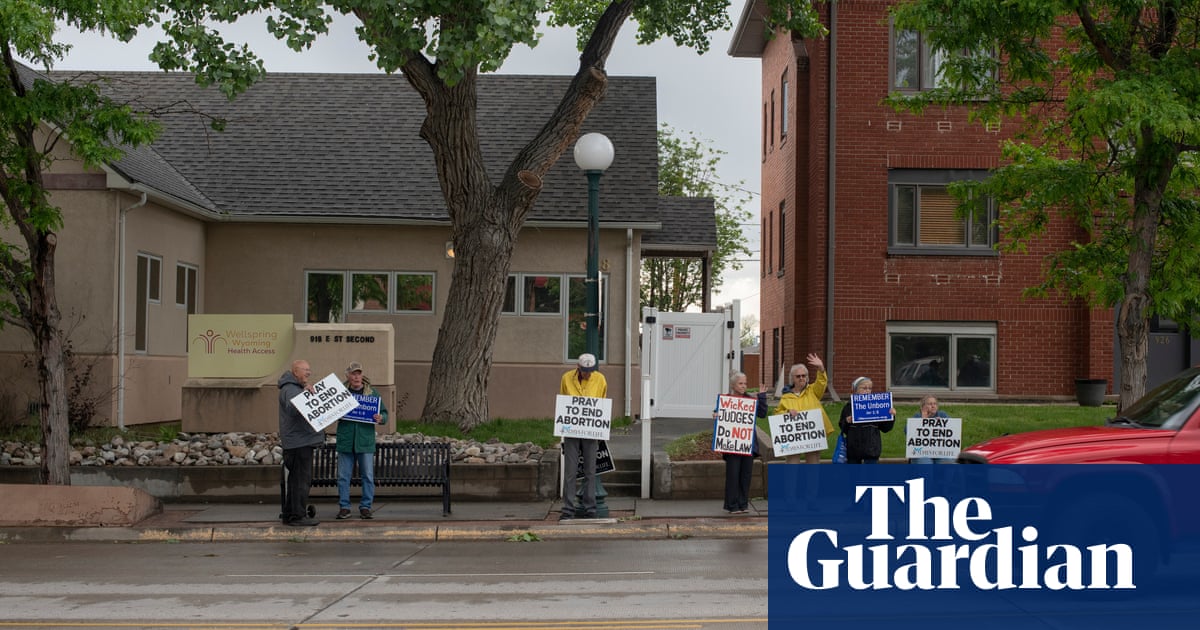

State judge Melissa Owens overturned Wyoming’s abortion bans in November 2024, citing the state’s constitutionally guaranteed right to healthcare. The Republican state senator Cheri Steinmetz and the bill’s eight co-sponsors took issue with the ruling, and sought to draw up a definition of healthcare that excludes abortion.

“The intent of [Senate File] 125 is to do no harm and go back to that Hippocratic oath and look at healthcare through that lens,” Steinmeitz told the Guardian.

Steinmetz says Senate File 125 offers a new definition of healthcare in Wyoming: “No act, treatment or procedure that causes harm to the heart, respiratory system, central nervous system, brain, skeletal system, jointed or muscled appendages or organ function shall be construed as healthcare.”

The bill carves out exceptions – for example, when such a procedure is required to save the life of a pregnant woman, or if “a person has no chance of meaningful recovery” without it. Fetal personhood is still on the books in Wyoming from 2023’s overturned “Life Is a Human Right Act”, but experts interviewed said that the murkiness of the bill’s language made it unclear if it would succeed at restricting abortion access – its intended purpose.

But Wyoming attorneys and healthcare law professionals at Boston University, George Washington University, Johns Hopkins and Pittsburgh University, say the problem is that a broad swath of healthcare procedures can be considered to cause “harm” by design.

“There’s a slew of medical procedures, surgeries, treatments that can have potentially positive outcomes but may also cause harm in the short period or as an unintended consequence,” the Wyoming attorney Abigail Fournier said.

“It’s scary to me, because I think it could be interpreted to be very limiting in terms of what healthcare providers can do.”

Wyoming’s constitutional right to healthcare stems from a 2012, voter-ratified constitutional amendment stating that “the right to make healthcare decisions is reserved to the citizens of the state of Wyoming”. Tom Lubnau, Wyoming attorney and former Republican speaker of the state house, helped author the amendment. He sees much of the current legislature as having “tunnel vision”, and a fixation on passing social issue legislation that ignores constitutionality.

“Healthcare decisions are the individual’s in Wyoming. And that’s what the freedom amendment says,” Lubnau said. “Butt out of my decisions, and let me take care of myself.”

Lubnau sits on one side of Wyoming’s gaping Republican divide, which pits an older class of more moderate, establishment Republicans against the state’s further-right Freedom Caucus, who, this past election cycle, became the first Freedom Caucus chapter to take control of a state house.

The Freedom Caucus has wasted no time in pushing a mass of social issue bills that line up neatly with national conservative talking points. Among the focuses are dismantling DEI programming, strict definitions of gender, immigration restrictions and a glut of abortion restrictions.

The Boston University healthcare law professor Nicole Huberfeld has seen plenty of crafty attempts to restrict abortion access, such as transvaginal ultrasound requirements, or laws mandating abortion clinics meet the licensing requirements of ambulatory surgical centers.

But Huberfeld and other experts interviewed said that they had yet to encounter a bill looking to redefine healthcare entirely.

Huberfeld will not be surprised if other states follow Wyoming’s lead, particularly those that have constitutional rights to healthcare.

“If they don’t have bills like this, I expect that they will take a page from Wyoming’s book and try the same thing,” Huberfeld said.

The George Washington University law professor Sonia Suter said the bill fit into a broader trend of taking away authority from medical professionals and putting it into the hands of politicians.

after newsletter promotion

“There’s a lot less faith in professional expertise, scientists, medicine,” Suter said. “Legislators are coming in and trying to pass laws that are less about healthcare and more about some kind of moral agenda, religious agenda. This is a way to sort of give the legislature more power.”

When asked if any doctors or medical professionals were consulted in the authoring of the bill, Steinmetz said that she received the bill from an attorney, and was not sure who the attorney sourced input from. She said that the bills’ sponsors were aware of concerns about chemotherapy and other procedures – and that they would sort it out if the bill moved forward.

“We have the best of intentions, and sometimes bills start out a little rockier than others,” Steinmetz said.

Joanne Rosen, health law professor at Johns Hopkins University, is less worried with the intentions behind the bill, and more so with the effects of bills that seek to carve out abortion – and end up affecting less “controversial” forms of healthcare.

“It has the effect of chilling physicians from administering medical treatment because they worry they may be in violation of the law. That’s a significant concern,” Rosen said.

While attorneys interviewed confirmed that voter referendums are necessary to make changes to Wyoming’s constitution, Steinmetz said that the bill did not seek to change the constitution – just a definition.

“Obviously it’s not spelled out in the constitution that abortion is healthcare, and so we can put limitations on that,” Steinmeitz said.

Still, Clark Stith, Wyoming attorney and former Republican state speaker pro tempore, is not sold.

“This bill, which purports to provide rules of construction of the Wyoming constitution, simply can’t do that,” Stith said. “A statute cannot change the meaning of words in the constitution. Period. End of story.”

Stith also wondered why, if abortion is such a central priority, politicians put the abortion question in the hands of Wyoming’s voters.

“Why aren’t you bringing it as a proposed constitutional amendment?” Stith asked. “Why aren’t you bringing it as a joining resolution to get placed on the ballot?”